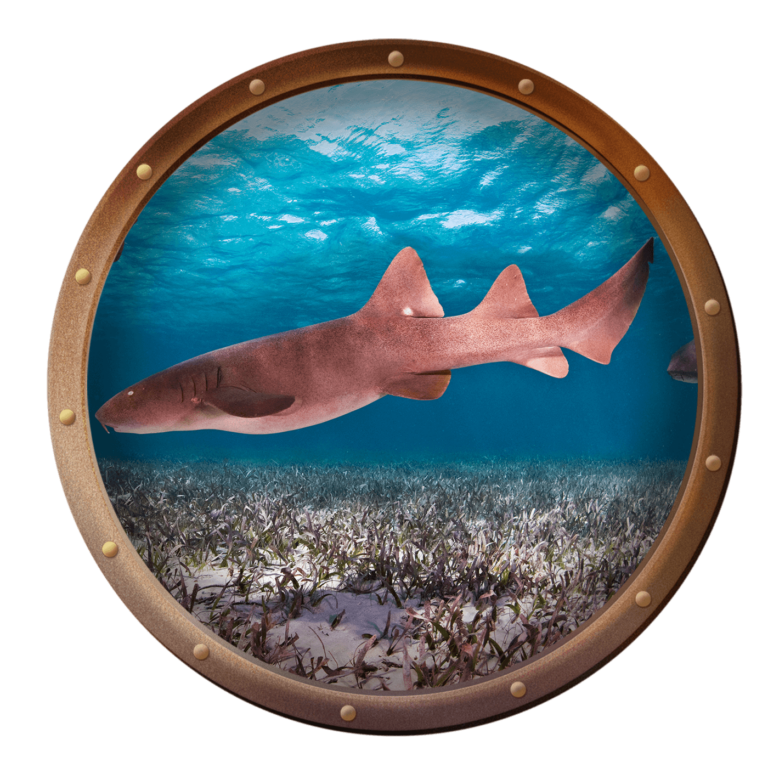

The nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, is the most common in the Florida Keys. Their abundance makes them an essential part of the marine ecosystem, where they significantly impact the population and distribution of their prey species. If you go snorkeling, diving or kayaking around Key West, you will likely see one or more of these charismatic sharks cruising the shallows or asleep on the bottom.

Nurse sharks are a benthic species that spend most of their time on the bottom. They are well-adapted for hunting prey hiding in the reef. They prefer shallow mangrove, seagrass, and coral reef habitats, which the Florida Keys have in abundance. Their small eyes, tough skin, flexible body and set-back dorsal fin allow them to wedge under rocks and mangrove roots to get at lobsters, fish and octopuses.

Their mouth is on the snout’s underside and lined with short fan-shaped, serrated teeth that crush hard-shelled animals. These teeth are set in rows and are replaceable. They grow continuously throughout the shark’s entire life, moving forward as if on a conveyor belt to replace teeth that are worn down or lost. This is a common trait among elasmobranchs, like sharks and rays, and is why it is common to find their teeth in the sand.

Nurse sharks use suction, created by their powerful buccal muscle and large pharynx, to capture prey. This suction force is powerful enough to pull a queen conch from its shell. The buccal muscle also allows them to pump water over their gills, a type of respiration known as “buccal pumping.” The fleshy, whiskerlike appendages on the mouth are called barbels. These sensory organs with taste and touch receptors help find prey on the bottom and in low visibility.

Shark social behavior is an emerging topic in scientific research. New technology is allowing scientists to make observations that were previously impossible to record, and increased interest in shark conservation and management has supported these efforts. The Florida Keys are a hot spot for nurse shark science. There are several ongoing studies, one dating back 30 years, about their reproductive and migratory behavior around the Dry Tortugas.

Long heralded as an important site for migratory birds, the remote group of islands known as the Dry Tortugas is also a popular nurse shark breeding ground. This was recognized as far back as the late 1800s, but scientific observations in the early 1990s provided invaluable data on the biology and behavior of the sharks that visited. This area sees an influx of adult nurse sharks every summer. Some sharks stay year-round, but others have been recorded traveling from as far as South Carolina or the Bahamas. The males are the first to arrive, showing up in April and May, followed by the females around June. By the end of July, the sharks typically retreat, but some females may stay through the fall or return in early October to December to give birth in the warm shallow waters.

The nurse shark is ovoviviparous, which means the female shark carries fertilized eggs in egg cases within her ovaries. The embryos receive nourishment from the yolk in the egg cases. Once this nourishment is depleted, the shark pups hatch from the egg cases and are born shortly after that. Nurse sharks have an average of 25-30 pups after a five- to six-month pregnancy. The 12-inch-long juvenile sharks are speckled for camouflage and use the mangrove roots as a nursery. After producing a litter, a female nurse shark takes two to three years to reproduce.

Caption: Pregnant Nurse Shark.

Nurse Sharks and Humans

The name “nurse shark” has unclear origins. The name may come from the sucking sound they make when feeding, which has been compared to that of a nursing baby. Alternatively, the name may come from an old word, “nusse,” meaning cat shark. Nurse sharks are considered non-aggressive and are generally not a threat to humans. They may bite defensively if stepped on or bothered by divers who mistake them for being docile. They are fast learners and opportunists, often gathering where fishing scraps are discarded or where they are fed intentionally. They can be bold and conditioned to the presence of humans, which makes them popular with tourists but dramatically increases the chances of a negative encounter. Some nurse sharks have also learned to follow people while they are spearfishing so that they can steal the catch. As with all wild animals, it is wise to keep your distance and remember that we are visitors to their home.

Currently, there is no commercial fishery for this species. Their fins are not sold, and while their meat is edible, it is not commonly consumed by humans and is sometimes used as crab bait. Nevertheless, nurse sharks are caught and killed by fishers in some areas, as they are considered a nuisance and interfere with the intended catch. They are considered pests in the Lesser Antilles, where they often invade fish traps. However, commercial anglers in the United States typically release nurse sharks alive. In the past, nurse sharks were sought for various reasons. Their liver oil was often used as fuel. Commercial sponge fishers also used their oil to calm the water surface, allowing them to locate sponges on the seafloor more readily. Their skin was considered the best of all elasmobranch species; being extremely tough and thick, it was used to make high-quality leather.