There are over 300 recorded species of octopuses worldwide! The octopus is a cephalopod, from the Greek words for “head-foot,” in the phylum Mollusca. There are two extant subclasses of cephalopods: the Coleoidea, which includes octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish, and Nautiloidea, which includes the Nautilus and Allonautilus. The coleoids either lost or internalized their shells, while the nautiloids still have external shells. Many octopuses have entirely lost any remnants of a shell, while squid have a pen and cuttlefish have a cuttlebone. This makes octopuses extraordinarily flexible and able to squeeze through small openings. They are only limited by their hard beak, which is made of chitin, the same protein crustaceans use for their shells. The sharp hooked beak is retractable and pulled up when not in use. Octopuses are carnivores; they eat other animals, primarily hard-shelled invertebrates like crabs and clams.

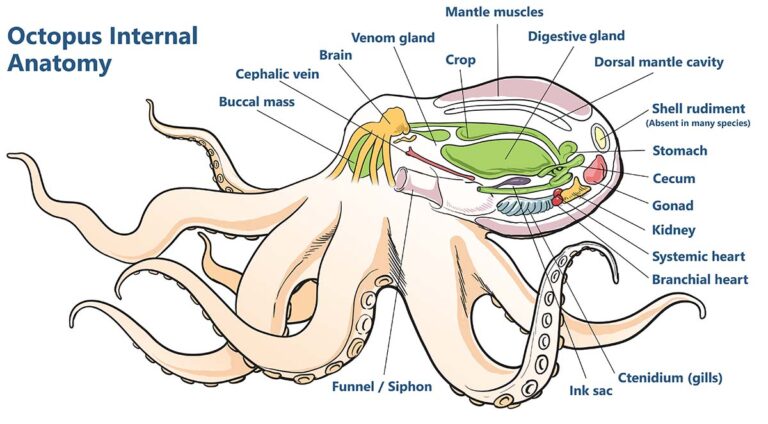

The beak sits inside the buccal mass, containing the pharynx (throat), salivary glands, and the radula. The radula is a ribbonlike structure made of chitin and covered in tiny teeth that octopuses use to drill holes into their hard-shelled prey. The beak acts like scissors, cutting flesh into larger chunks while the teeth on the radula shred it into smaller swallowed pieces. The salivary glands are connected to venom glands, producing paralytic toxins that are especially effective on crabs and clams. Venom is injected into the hole made by the radula, which paralyzes the prey, keeping the octopus safe from pinching claws and relaxing muscles that hold shells closed. All octopuses are venomous; however, most are not dangerous to humans. There are some notable exceptions, though! The blue-ringed octopuses, which comprise the genus Hapalochlaena, are famously deadly. They have extra toxic compounds in their venom, including tetrodotoxin, a powerful paralytic they share with some pufferfish. Fortunately for visitors to the Florida Keys, these octopuses are native to the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Octopuses are clever creatures! They are the most intelligent invertebrates, with around 500 million neurons, about the same as a dog! The reason for this high level of intelligence most likely developed due to losing their shell. Shells are heavy and energetically costly, but they provide high protection. Losing their shell meant octopuses were faster and nimbler but more vulnerable to predation. The ability to plan, problem-solve, manipulate objects, use tools, recall memories and camouflage has allowed octopuses to be effective predators while avoiding becoming prey themselves.

Octopuses have a doughnut-shaped central brain so that the esophagus can pass through. The brain controls higher executive functions, like decision-making, complex movement, and memory, but only has one-third of the total neurons! The other two-thirds are in their eight arms, which can move and act independently, even after they have been severed!

Each arm has 200-300 suckers with a muscular outer ring and a chamber in the middle. The outer ring forms a tight seal when it presses against a surface, then the chamber contracts to create negative pressure and suction. Each sucker can move and grasp on its own! They also have chemical “taste” and mechanical “touch” receptors that send information through the nervous system to the brain.

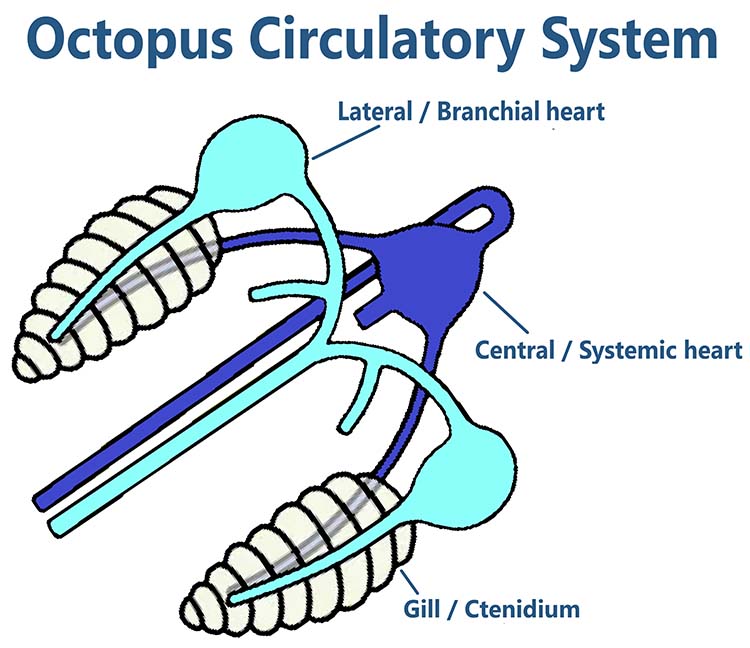

Octopuses have blue blood and three hearts! The blood is blue thanks to hemocyanin, which uses copper rather than iron to transport oxygen. This is more efficient in cold and low-oxygen environments than iron-based hemoglobin, which is perfect for the ocean! The three hearts function very similarly to the four chambers that humans have in their hearts. The lateral or branchial hearts pump blood to the gills, where oxygen is received. The blood pressure from the gills is too low to pump blood around the body, so the central or systemic heart increases the blood pressure. Octopuses have been recorded pausing the systemic heart at rest and while swimming. It is yet to be fully understood why they do this, but it is likely related to blood pressure. When an octopus rests, the pressure from the branchial heart is strong enough that the central heart is not needed. Octopuses swim quickly using jet propulsion; water is forcefully expelled from inside the mantle cavity through the siphon. The pressure inside the mantle cavity from the water and muscular contraction is so high that the central heart can’t work against it. This quickly leads to a deficit of oxygen and is one of the reasons that octopuses prefer to use their arms to move rather than swim.

Octopuses are masters of camouflage!

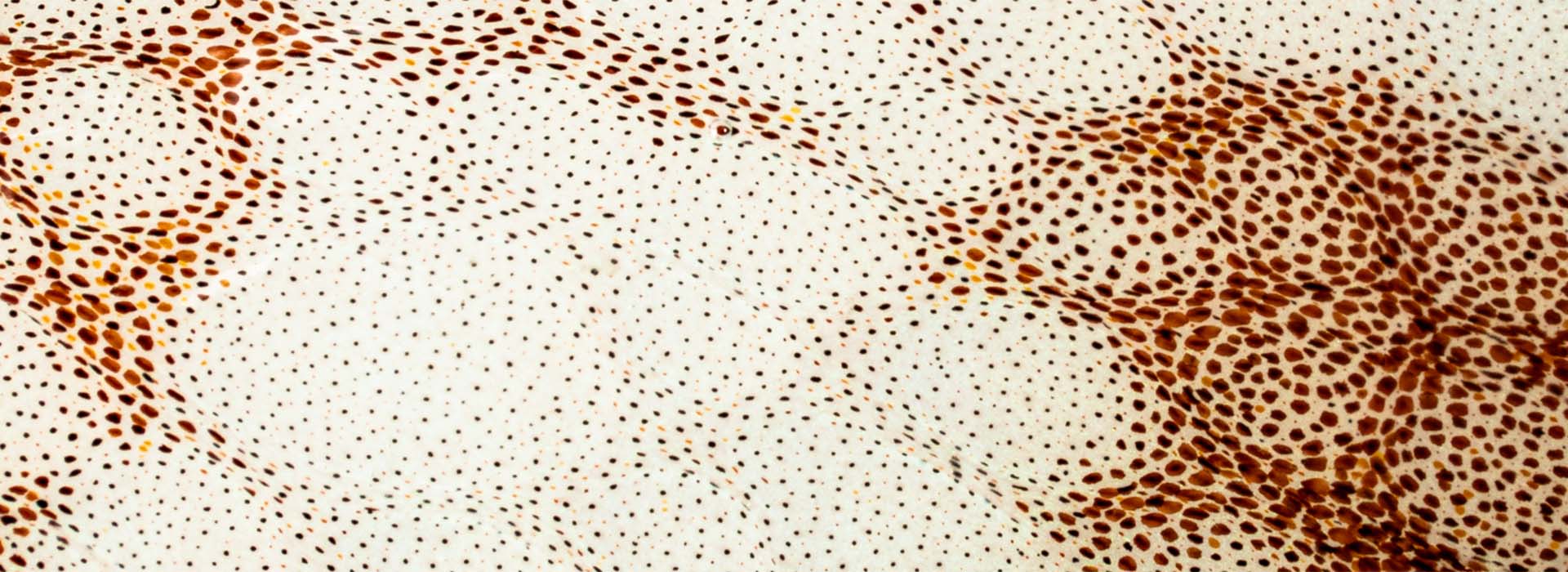

The success of these creatures is owed mainly to the ability to blend in with the environment or use deception to fool predators. Octopuses can change the color and texture of their skin almost instantaneously. The texture is created when the brain signals to contract muscles, raising bumpy structures called papillae. Color and pattern are controlled by specialized structures under the skin. Chromatophores are small organs that contain sacs of pigment which create red, yellow, and brown colors. When muscle fibers surrounding the chromatophore contract, the pigment sac is opened and visible through the skin.

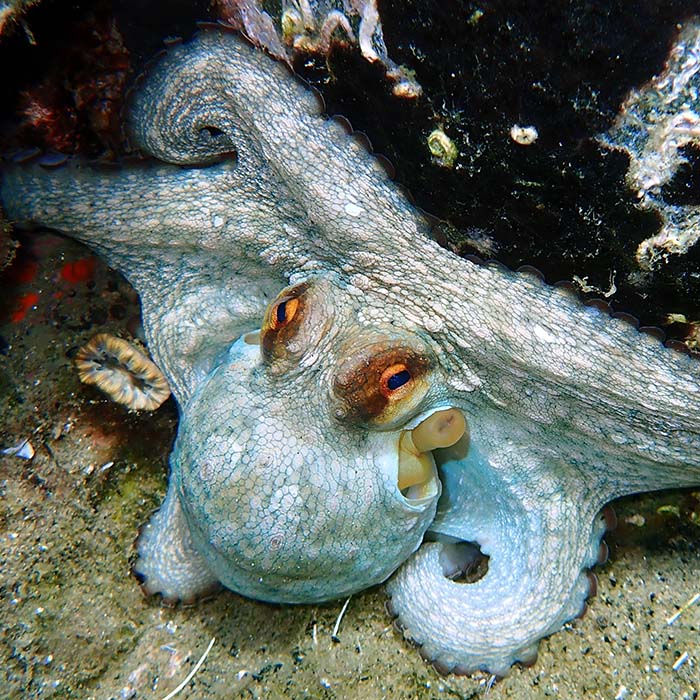

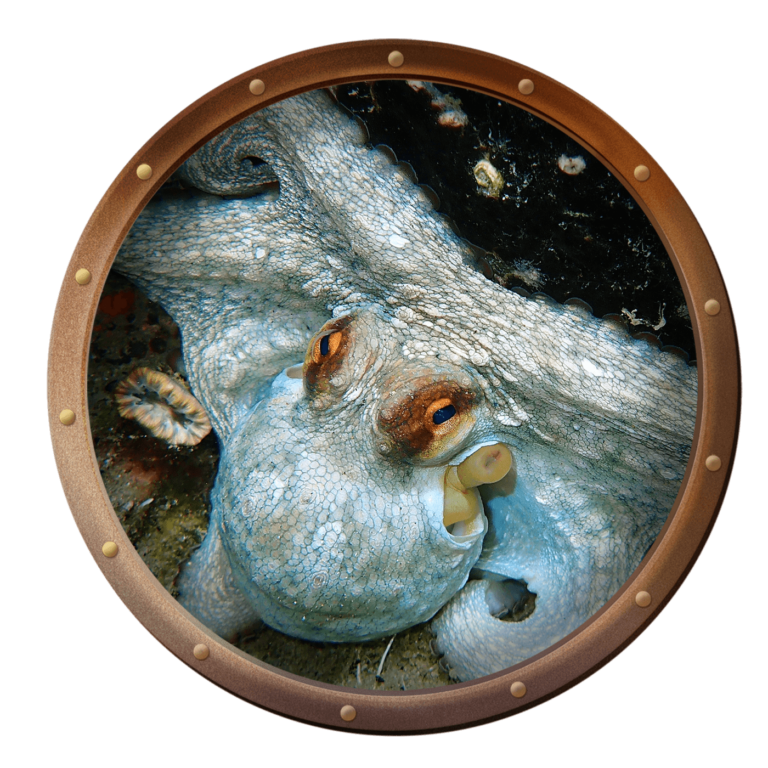

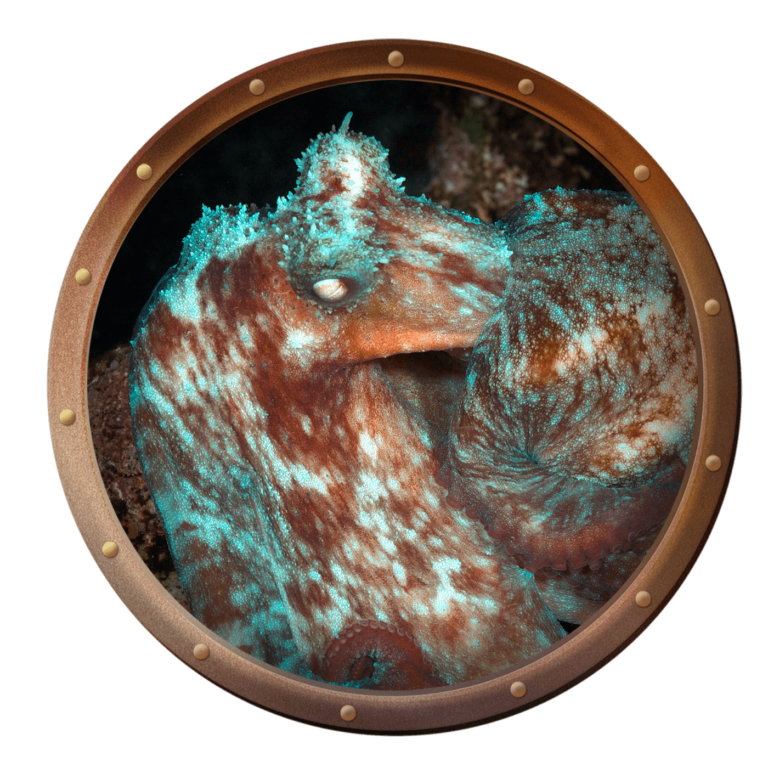

Photo caption: Common octopus, Octopus vulgaris, changes from smooth white to highly textured and colored to blend in with the reef.

If changing their color and shape isn’t enough to evade predators, octopuses have another trick: ink! Most octopuses have glands that create a dark ink, which is stored in the ink sac. The main pigment is melanin, which gives the ink its black color. An octopus fleeing a predator can shoot ink mixed with mucus out of its siphon. The ink cloud creates a “smoke screen” that distracts and obscures a predator’s vision, allowing the octopus to escape. The thick mucus can create an octopus look-alike called a pseudomorph that hangs in the water while the octopus jets away in another direction. In addition to the camouflage and distraction functions, the ink also contains a chemical called tyrosinase, which is a powerful irritant that can disrupt a predator’s sense of smell and taste and even cause blindness!

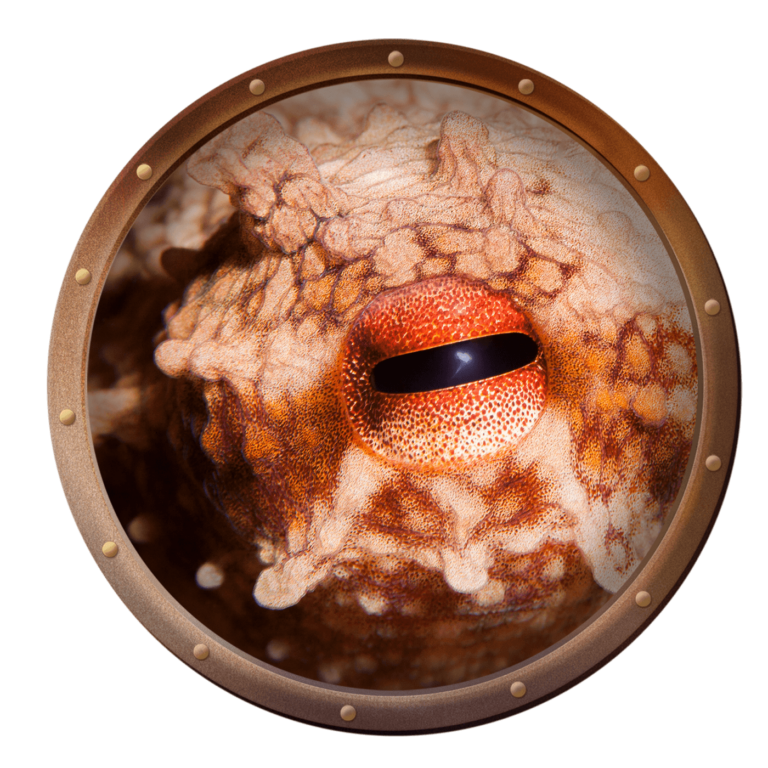

Octopuses have excellent eyesight and eyes that are very similar in structure to those of humans. This is an exciting example of how similar structures and functions can develop independently in distantly related species due to similar environmental or behavioral pressures. Humans and octopuses have single-chambered camera-type eyes. They consist of a globe that contains vitreous fluid, a circular lens, an iris, pigment cells, a retina and photoreceptor cells that translate light into nerve signals. The significant difference between human eyes and those of octopuses is where the nerve fibers connect with the optic nerve. Humans have a blind spot where the nerve fibers pass through the retina to communicate with the optic nerve, while the nerve fibers pass behind the retina in octopuses. Focus is achieved by movement of the lens, much like a telescope, rather than changing the shape of the lens as in human eyes. An autonomic response causes the pupils to remain in a horizontal position no matter the body’s orientation. Despite having amazing color-changing abilities, many octopuses are colorblind! Colors are sensed by opsins, photoreceptors in the skin, allowing octopuses to match their environment without seeing it themselves.

Photo caption: Closeup of the eye of a common octopus, Octopus vulgaris

Octopuses tend to have relatively short life spans; most reproduce only once and die soon afterward. Mating can be dangerous as well; if one of the pair is not interested, the other may end up as a meal! Some species have elaborate courtship displays to gauge interest and signal intent. The male octopus uses a modified section of an arm, called a hectocotylus, to transfer a spermatophore into the female’s oviduct, which will be stored until she is ready to lay eggs. This structure may also remove spermatophores from previous mating. Males mate only once and usually die within a few months after doing so. Females may mate more than once but typically lay eggs not long after mating. This begins a period of intense parental care and a process called senescence. Laying eggs triggers hormonal changes in the optic gland, which stops the females’ urge to eat. Interestingly, mating causes the same change in male octopuses even though they do not participate in parental care.

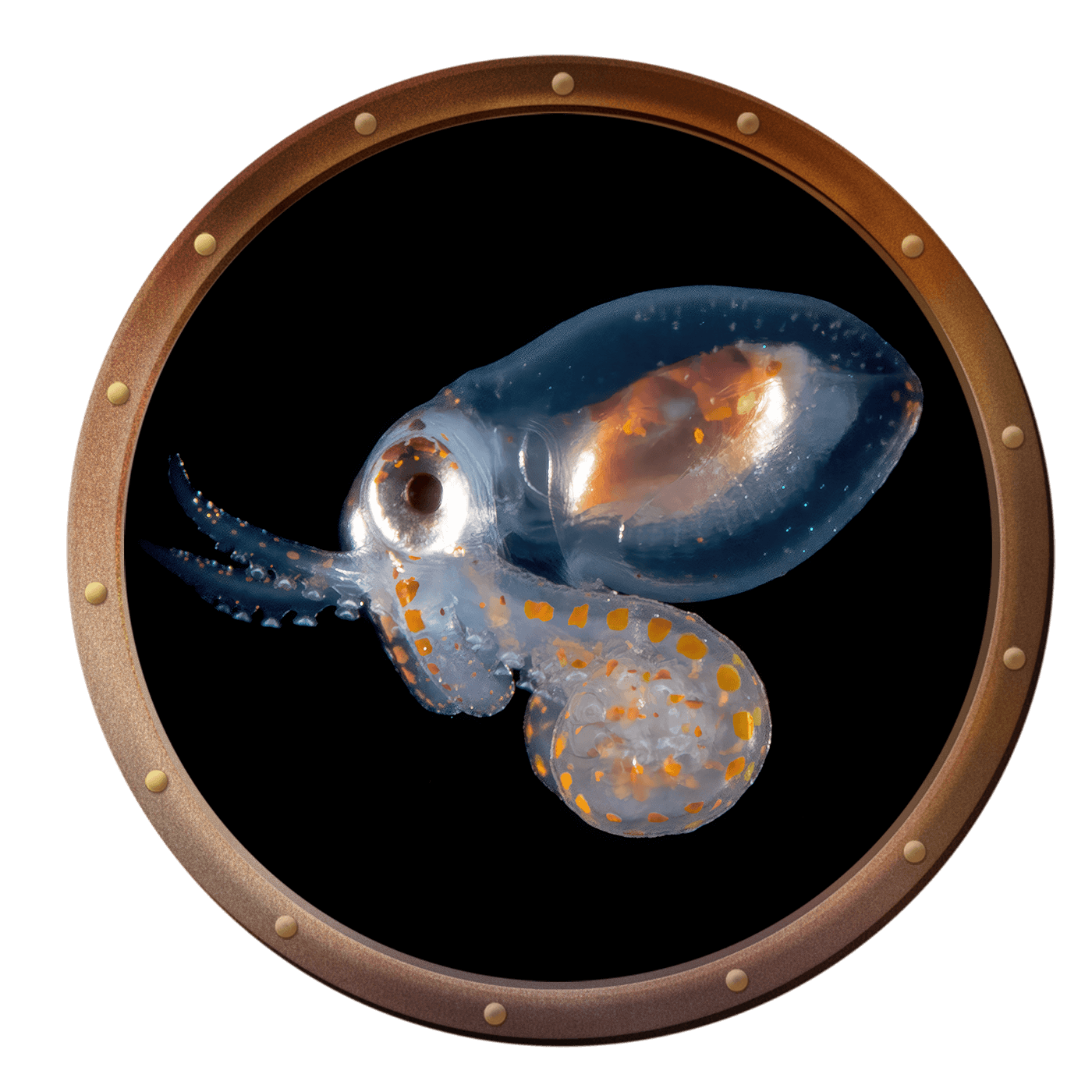

Left to right: Common octopuses, Octopus vulgaris, mating. Female common octopus, Octopus vulgaris, with eggs. Octopus larva

Octopuses in Florida

Caribbean Reef Octopus, Octopus briareus

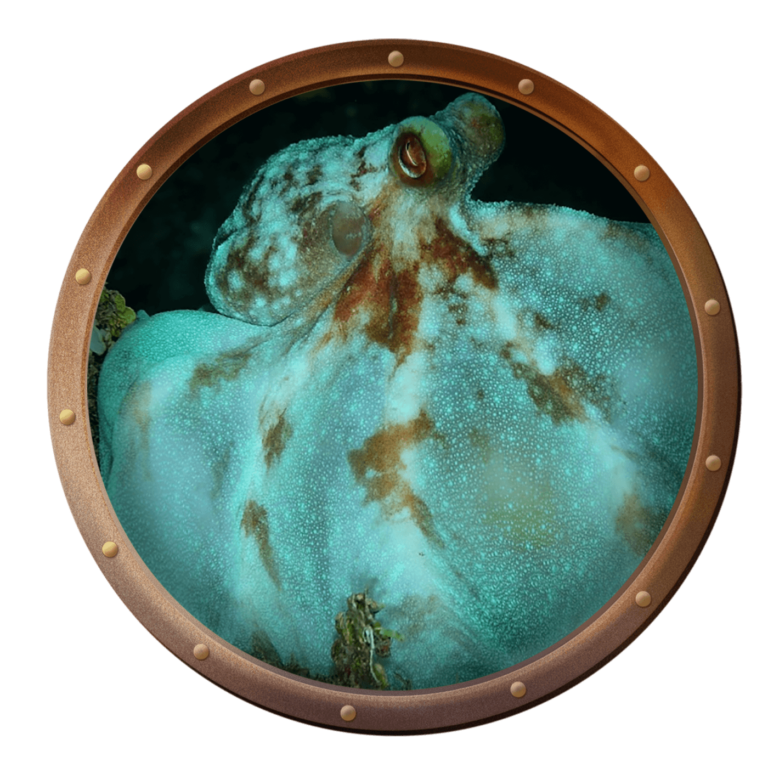

The Caribbean reef octopus, Octopus briareus, can be found in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. It prefers shallow waters, typically fewer than 75 ft, with complex reef and rock structure; but it also ventures into seagrass and rubble habitats. It has a small head but can reach 2 ft long with its arms extended. This species showcases striking blue-green iridescence when its chromatophores are retracted.

The Caribbean reef octopus is a nocturnal predator that catches prey by making a parachute with its arms, often covering an entire coral head! It feels around with the ends of its arms to grab any prey and move it to its mouth. They are not picky eaters, feeding on crabs, shrimp, spiny lobsters, clams, benthic worms and small fish.

The Caribbean reef octopus has a short life span, just 10-12 months, typical for warm-water species. Males reach reproductive maturity after only 140 days, and females after 150 days. The female lays about 200-500 eggs at a time, which develop for 50-80 days. Although they lay fewer eggs than most octopus species, the eggs are larger, and the babies are born as mini versions of the adults, ready to start hunting as soon as they hatch!

Common Octopus, Octopus Vulgaris

The scientific name for this species, Octopus vulgaris, literally translates to “common octopus.” This name has been used to describe four octopus species divided by geographic region, making up the O. vulgaris species complex. This includes O. vulgaris type I (Caribbean Sea and North America), type II (along the coast of Brazil), type III (along the coast of South Africa) and type IV (Japan). Recent studies using genetic samples and molecular analysis suggest that this group has six species. Although these groups have different geographic ranges and genetics, they have similar behaviors and appearances.

The common octopus lives in tropical and subtropical seas and can be found at depths from 0 to 650 ft from the shore all the way out to the continental shelf. It prefers habitats with complex bottom structures, where it can easily use camouflage to blend in with the surroundings.

The common octopus is adept at changing color, pattern and texture to blend in with its surroundings. They employ a “walking rock” or “walking algae” strategy to move across the bottom without being detected. Their diet is mainly composed of crustaceans and mollusks like clams and snails. After catching prey, this species returns to its den to eat, often piling the remains outside the entrance in a midden pile. This little refuse heap helps block the entrance to the den but is also an excellent way for scientists to study what the octopus is eating and to locate the den. This species tends to be more active at night, but this varies depending on location and competition with other species.

The common octopus has a 12- to 18-month lifespan and typically spends its entire life in the same den. The female common octopus lays 100,000 to 500,000 eggs! The eggs are about the size of a grain of rice and are attached to strings hanging from the den’s roof. The devoted mother cleans and blows water over the eggs, rarely leaving the den while the eggs develop. This can take six weeks in warm waters and up to five months in colder waters. She stops feeding and will die after the babies hatch, having lost one-third of her body weight. The tiny octopus larvae spend the first 1½- months in the water column as part of the plankton. They are miniature adults but don’t have all eight arms yet! It takes about 60 days for them to grow all of their arms and settle out of the water column.

The common octopus is highly intelligent, able to solve puzzles and mazes, and recognize different human faces. This species has been an essential contributor to science, used as a model species for studies on cognition, developmental biology, neuroscience and more. Its popularity as a laboratory subject and evidence of its intelligence led to it becoming the first invertebrate animal protected by the “Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986” in the United Kingdom too!

Atlantic White-Spotted Octopus, Callistoctopus Macropus

The Atlantic white-spotted octopus has a circumglobal range in warm-to-temperate waters. It is also known as the grass octopus and grass scuttle. This species is a nocturnal predator, leaving its den after dark to search for prey. It creeps along the bottom, using its sensitive arms to search between corals and inside crevices. Opportunistic fish will follow the octopus as it hunts, hoping to catch any small fish or invertebrates that escape it.

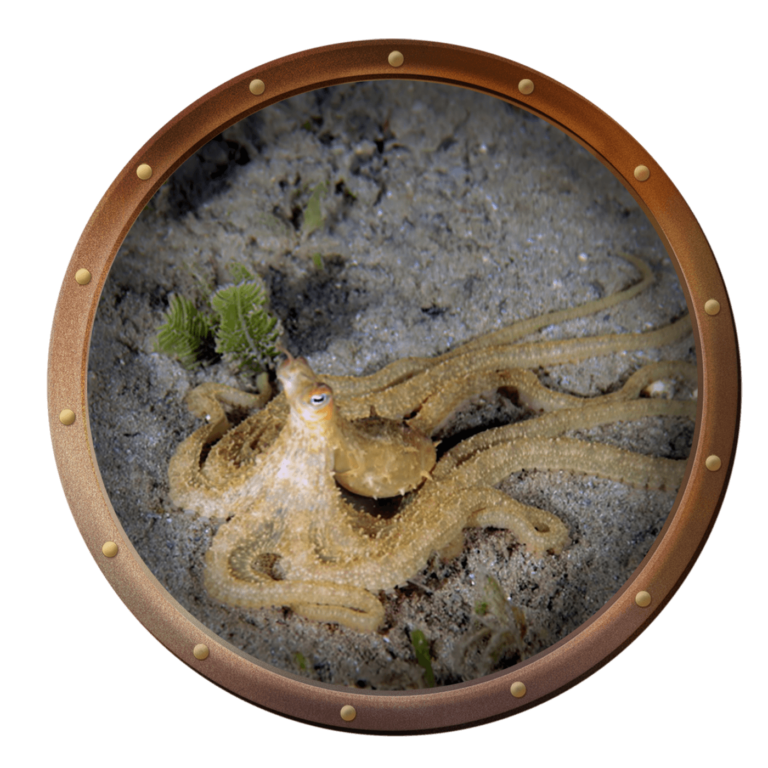

Atlantic Longarm Octopus, Macrotritopus Defilippi

The Atlantic longarm octopus, also known as the Lilliput longarm octopus, is a small, sandy, and muddy bottom-dwelling species. As its name suggests, the arms of this octopus are very long and can be up to seven times the length of its body! This species can burrow in the sand while hunting or to escape predators. Before leaving the safety of its den or hiding place, the Atlantic longarm octopus “stands up” in a tripod position to survey the area.

It uses multiple forms of camouflage, including changing its color and texture to match the sand- or algae-covered bottom and mimicry to look like a flounder while swimming.

The Atlantic longarm octopus can be found in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and in the Mediterranean Sea. However, this is likely a species complex with more than one member. This species has an overlapping range with the common octopus, Octopus vulgaris, in Florida, which has been the subject of research. The two species can coexist in the same areas because they are active at different times of the day and have different diets. The common octopus prefers hard-shelled mollusks and crabs, is active at night, and lives in rocky areas, while the Atlantic longarm octopus hunts for crustaceans like sand crabs and shrimp in sandy areas during the day. This is an example of how two species that are similar in biology can avoid competition.