One of the most popular tours at the Key West Aquarium is the Sea Turtle Conservation Tour. In this tour, we introduce you to our rescued turtles, who are now living with us because they wouldn’t survive out at sea. The species of sea turtles at the aquarium can all be found in Florida waters! Florida is a major nesting destination for sea turtles on both the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts. Turtle nesting in the Florida Keys is most active at Dry Tortugas National Park, named after the abundance of sea turtles that visit. Park biologists have monitored sea turtle nesting activity within park boundaries since 1980.

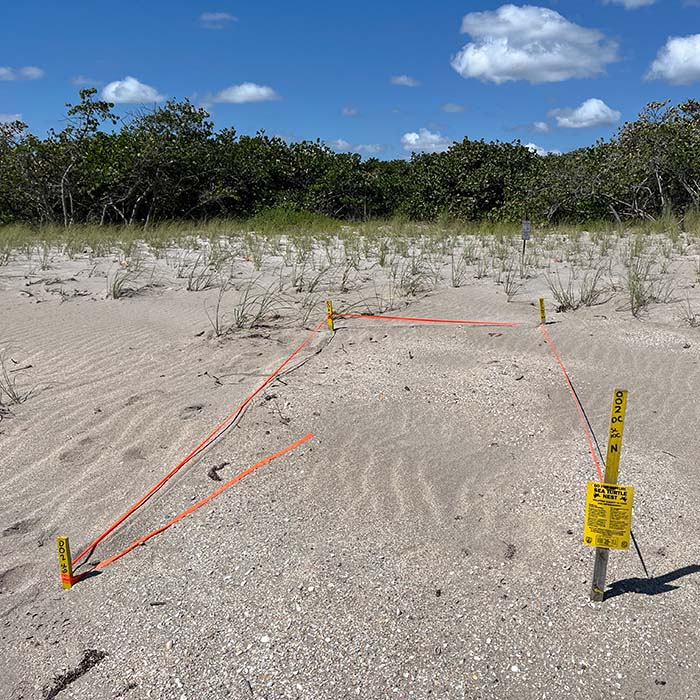

Sea turtle nests are found by looking for tracks, or crawls, to and from the ocean and mounds of sand in a distinctive shape. Each sea turtle leaves a different pattern of tracks, which helps identify the species that laid the nest. Nests are marked, recorded and checked for signs of hatchlings, beginning about 45 days later.

Sea turtle eggs are comparable to Ping-Pong balls. Post-hatch, biologists will uncover the nest to identify and record hatched and unhatched eggs, how many turtles are alive, and other signs of natural predators or disturbances. Incubation takes about 60 days and depends on the sand’s temperature for the embryo’s development speed. Temperature also determines the sex of the hatchlings, with temperatures below 81.86° Fahrenheit resulting in males and temperatures above 88.8° Fahrenheit resulting in females. This has historically resulted in a fairly even ratio of males to females in a nest, with the eggs at the bottom of the nest developing into males and those closer to the top developing into females. Increased temperatures in recent years have caused a shift in the sex ratio, resulting in more females and fewer males, with nests in some areas only producing females.

Natural threats to young and adult sea turtles are abundant, but increasing human threats are driving them to extinction. The U.S. federal government keeps a catalog of threatened, endangered and extinct species. Loggerhead sea turtles remain threatened, while the remaining sea turtles found in local waters are endangered. Nonnatural threats to sea turtles include vessel strikes, being caught as bycatch in fishing gear, the loss and degradation of nesting habitat, direct harvest of turtles and eggs, and ocean pollution/marine debris.

It Is Illegal To Disturb Sea Turtles and Sea Turtle Nests!

To report someone disturbing a sea turtle nest or an injured, dead or harassed sea turtle, call 888-404-FWCC (3922). Cellular phone *FWC or #FWC.

Loggerhead Sea Turtle, Caretta caretta: Threatened

This species is named for its large blocky head and powerful jaws. The term “logger” refers to a heavy block of wood traditionally used to hobble horses and later attached to the stern of a whaleboat, around which the harpoon line is passed. The earliest documented usage referring to the sea turtle was in 1595. This species typically grows to 275 lbs and 3 ft across but can get much larger. The biggest loggerhead on record weighed 1,201 lbs! Loggerhead turtles have a heart-shaped carapace (shell) without ridges and large non-overlapping, rough scutes (scales) with five lateral scutes. The front flippers are short and thick with two claws, while the rear flippers can have two or three claws. They have a characteristic reddish-brown carapace with a yellowish-brown plastron (belly). Hatchlings have a dark brown carapace and flippers with pale brown on the margins. Loggerheads are primarily carnivorous and feed mainly on shellfish living on the ocean’s bottom. They eat horseshoe crabs, clams, mussels and other invertebrates. Their powerful jaw muscles help them to crush the shells of large marine snails like whelks and conchs.

Green Sea Turtle, Chelonia mydas: Endangered

The green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas, is not named for the color of its shell but for the green body fat that it develops due to its mainly vegetarian diet of seagrasses and algae. Once prized for its meat, fat, and eggs, it was nearly wiped out by the early 1900s. Conservation efforts have had positive effects, and green sea turtle nests in Florida have increased by 80 times since standardized nest counts began in 1989. A new state record was set in 2023, with more than 76,500 nests counted!

Green sea turtles can grow very large and compete for the “largest hard-shelled turtle” title with the loggerhead. Adults average 240-420 lbs, with shells between 33-45 inches long. The largest-ever recorded green sea turtle was 5 ft long and weighed 871 lbs! This species lives long, with a natural life span estimated to be over 70 years. As hatchlings, green sea turtles go to the open ocean and use floating seaweed as a shelter and hunting ground. They feed on small invertebrate animals like shrimp, crabs, and jellies and vegetation like algae and seagrasses. Once the juveniles reach 8-10 inches in length, they undergo a shift in diet, becoming facultative herbivores. They have a primarily vegetarian diet but won’t pass up an easy opportunity for a protein meal.

Green sea turtles feed on algae and seagrasses that grow in coastal marine waters, with one type of seagrass so popular with this species that it is called “turtle grass.” Once green sea turtles switch to an herbivorous diet, they stick with either algae or seagrass as their primary food source rather than switching back and forth. It is thought that this may be related to the types of bacteria that live in the turtle’s gut and digest the material. Different bacteria are required to break down algae versus seagrass.

Green sea turtles can be differentiated from other sea turtle species by the four costal scutes on either side of their carapace and the single pair of prefrontal scales on their heads. The coloration of young turtles tends to be more varied than that of adults, with characteristic “sunburst” patterns on the scutes.

Leatherback Sea Turtle, Dermochelys coriacea: Endangered

The leatherback is the largest, deepest diving, most migratory and wide-ranging sea turtle. Adult leatherback turtles can grow 4-8 ft long and weigh 500-2,000 lbs. The leatherback is named for the structure of its shell. Rather than hard bony plates, the shell of this species has small bones with a firm, rubbery skin on top and seven ridges down the carapace. This allows flexibility so that the shell can withstand the crushing pressure of the deep ocean. They have been recorded diving to 4,000 ft and can stay down for 85 min. The leatherback is predominantly black with varying pale spots. Adult leatherback sea turtles have a pink spot under their chin. They have a toothlike cusp on each side of the upper jaw and backward-pointing spines in their mouth and throat. These are ideal for catching gelatinous prey like jellyfish and salps.

Photo attribution: ©Emilie Ledwidge/Ocean Image Bank

Hawksbill Sea Turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata: Critically Endangered

The hawksbill is a small- to medium-sized marine turtle with a long oval shell and overlapping scutes on the carapace. Their relatively small head with distinctive hawklike beak and flippers with two claws make them easy to identify. An adult hawksbill’s carapace is brown with yellow, orange or reddish-brown notes, with a yellowish underside patterned with black spots on the intergranular and postanal scutes. Juveniles present as black or very dark brown with light brown or yellow coloration on the edge of the carapace, limbs, and raised ridges. As an adult, the hawksbill may reach up to 3 ft in length and weigh up to 300 lbs, although adults more commonly average about 2½ ft in length and typically weigh around 176 lbs or less. They are the only sea turtles with two pairs of prefrontal scales and four pairs of costal scutes.

Hawksbill sea turtles are named for their beaks’ distinctive hook shape, which they use to graze on coral reefs. They are omnivores, eating plants and animals, but have the rare ability to eat sponges. Sponges often produce toxic chemicals and have an internal structure that is difficult to digest, making them unappealing to most creatures. However, an adult hawksbill can consume an average of 1,200 lbs of sponge a year! This makes hawksbills important regulators of sponge growth on coral reefs, preventing sponges from overgrowing and outcompeting corals for space.

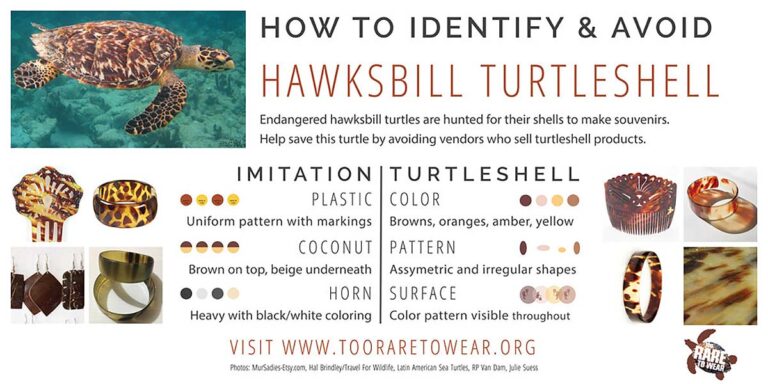

Hawksbill sea turtle shell has long been prized as a material for jewelry, accessories, furniture inlays, eyeglass rims and more. Before the invention of plastic, the scutes from hawksbill sea turtles were the primary source of the misnamed “tortoiseshell” material. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 banned the import, export or trade of this material in the United States, but it is unfortunately still used in other countries. Although there are regulations and prohibitions on the harvest of hawksbill sea turtles in other countries, poaching is still a major issue and one of the biggest threats to this species. Be very careful when buying souvenirs while visiting the lower Caribbean, Central and South America (particularly Nicaragua), and countries in East Asia. It can be hard to distinguish between genuine sea turtle shell material or plastic if you are not looking for it, and items are not necessarily costly. Check out this great graphic from the Too Rare To Wear campaign for tips on how to tell the difference between turtle shells and other materials.

Photo attribution: Hal Brindley / TravelforWildlife.com

Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle, Lepidochelys kempii: Critically Endangered

The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle has a triangular-shaped head with a slightly hooked beak equipped with large crushing surfaces. The almost circular carapace in adults is grayish green, while the plastron is pale yellow to cream. Hatchlings are black on both sides, in contrast to the adults. The carapace is often as broad as it is long and contains five pairs of costal scutes. Each front flipper has one claw, while the back flippers may have one or two. Swimming crabs make up the majority of their diet, but Kemp’s ridleys also eat fish, jellyfish and mollusks. Foraging zones range from the Yucatán Peninsula to southern Florida.

This species was initially thought to be a hybrid between the more common loggerhead and green sea turtles, but a local Key West man named Richard M. Kemp thought otherwise. He submitted the turtle for identification in 1880, and they are named in his honor! Kemp’s ridleys are the smallest species of sea turtle, only reaching 100 lbs, and they are the rarest species. They also have a unique nesting behavior that remained a mystery for many years. It wasn’t until 1947 that an aerial survey over a stretch of beach in Rancho Nuevo, Mexico, revealed where and when this species lays its eggs. Forty-two thousand female Kemp’s ridley sea turtles were documented nesting on a single beach during that survey.

Kemp’s ridleys nest as a group during daylight hours in a synchronized event known as an “arribada.” This strategy overwhelms the potential predator population on the beach and means that the babies will hatch at the same time as well, giving them a better chance to make it out to the open ocean. Nesting during daylight hours also avoids nocturnal predators like raccoons and coyotes. They nest on only a few beaches, with only three in Tamaulipas, Mexico, hosting 95% of Kemp’s ridley nests. Unfortunately, this strategy makes them very vulnerable to humans harvesting them. By 1991, only 200 females were documented nesting on those beaches. There is good news, though! Due to conservation efforts and legislation to protect their nesting habitat, Kemp’s ridley numbers are rising.

Photo attribution: By Hrchenge – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.