The queen conch, Aliger gigas, is a large marine snail that can be found throughout the shallow waters of the Caribbean, the Florida Keys, and north of St. Lucie Inlet. It is the largest of the six species of “true conchs” that can be found here. Conch snails have a characteristic shape to the front of their shells known as the “stromboid notch,” through which they extend their eye stalk. They have highly developed eyes and excellent vision. Branching from the eye stalks are tentacles that sense chemicals in the water, leading them to their favorite foods.

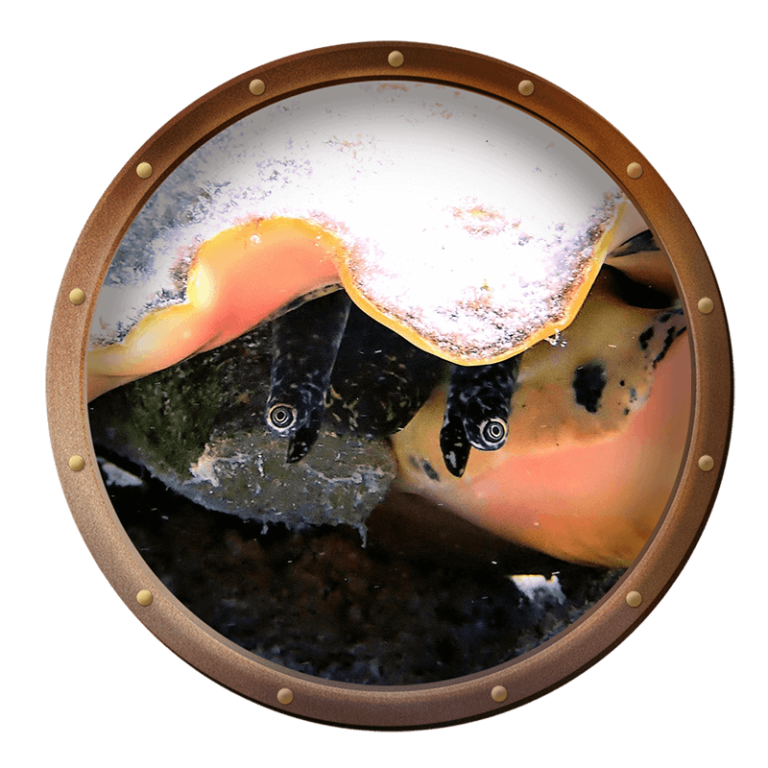

These snails have a large muscular foot with a sickle-shaped operculum that they use to hop along the sea bottom and right themselves if they get flipped over. The operculum, made of hardened protein and attached to the back of the foot, digs into the sea floor and allows conchs to propel themselves like pole-vaulters. This “stromboid leap” may help break up the scent trail left by the snails and allow them to more quickly escape predators. The operculum also acts as a door by blocking the entrance to the shell when the snail retracts its body inside.

Queen conchs have a long extendable proboscis that they use for feeding. It looks much like the trunk of an elephant and is quite mobile. The mouth is at the end of the proboscis and contains the radula, a tongue-like structure covered in tiny teeth used to scrape food particles off surfaces. Conch snails are herbivorous. They feed on red and green macroalgae, especially Laurencia spp. and Batophora oerstedii, as well as detritus and diatoms associated with turtle grass, Thalassia testudinum. The extensive seagrass meadows surrounding the Florida Keys are the perfect habitat for queen conchs.

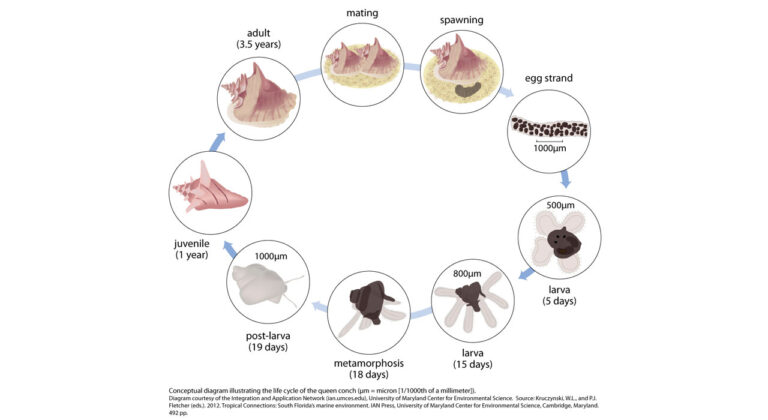

Life Cycle of the Queen Conch

Queen conchs have separate sexes and mature after 3.5-4 years. Adult male and female snails gather in groups during the reproductive season, typically a six to eight month period beginning in March and ending in October. Conchs have internal fertilization, after which the female will lay an egg mass in the shape of a crescent. This can have 400,000 eggs, and females may produce nine egg masses in a season, totaling 3-4 million eggs a year. If abundant food is available, older females may lay even more eggs in a season. The eggs are coated in sand to help camouflage them until they hatch after three to four days of incubation. The first stage of life occurs in the water column, as part of the plankton. Conchs hatch as veliger larvae and drift for three to eight weeks as they develop. Once they reach a minimum shell length of 1-2 mm, they are ready to settle onto the bottom. The veliger larvae respond to chemical cues in the water to choose where to settle; the smell of their food source guides them to seagrass beds. Once they settle to the bottom, they undergo metamorphosis and grow their iconic shells. Queen conchs have a relatively long life span, with individuals in the Caribbean able to live for 40 years or more. However, those in Florida have a much shorter life span, estimated at seven to 15 years.

How Do Conchs Build Their Shells?

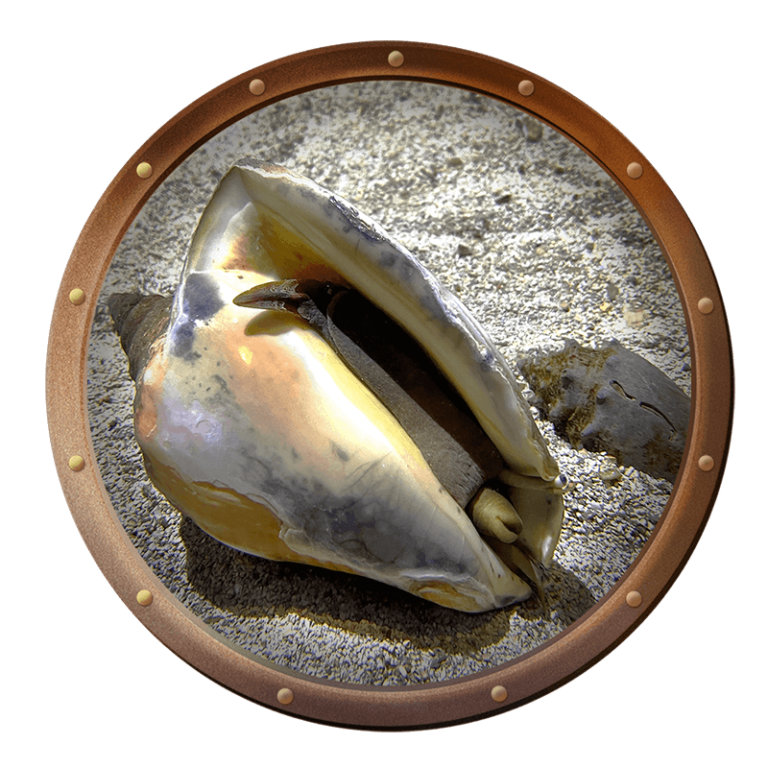

Conch snails grow their own shells. It is a part of their bodies (unlike hermit crabs who occasionally make their homes in discarded conch shells) and can reach up to 1 foot in length and around 5 lbs, making them the largest herbivorous snail in the Western Hemisphere. The shell grows lengthwise in a spiral pattern for 2.5-3 years or until it reaches about a foot. Then the orientation of shell growth flips to make a broad lip. This makes the snail very stable and hard to flip over. They will continue to add thickness to the shell once they have reached full length and width for the rest of their lives. Mature queen conchs are called “broad lips” due to this structure, while younger snails are called “rollers,” since waves can roll them up onto the beach. Conchs build their shells through a process called biomineralization. They use elements from the water and the food they eat to create hard shells in much the same way that our bodies grow bones and teeth.

The shell is secreted in layers by the mantle, the orange skirt-like tissue that surrounds the body of the snail in the shell. The shell is mainly composed of calcium carbonate, which is a strong but brittle mineral. Thin layers of proteins between the sheets of calcium carbonate give the shell strength by allowing microcracks to form in response to pressure. The combination of the two materials, and the direction in which they are laid, makes the shell very hard. This same process may also result in a pearl. If a foreign body becomes lodged in the mantle, a protective layer of shell is secreted to wall it off. Conch pearls are rare, only occurring in 1 in 10,000 snails harvested. A gem-quality pearl is even more rare, occurring in about 1 in 100,000 snails, making them very valuable. They can come in a range of pinks, oranges, and browns, and some even have a flame-like structure called chatoyancy.

Queen Conch History and Future

The queen conch is the unofficial mascot of Key West and is well-represented throughout the island. The people who are born on the island of Key West are called “Conchs,” and the island itself is referred to as the “Conch Republic” in homage to the snail that was once highly abundant in nearshore waters. Three thousand years ago, the shells of queen conchs were used by the indigenous Arawak peoples as musical instruments, tools, ceremonial objects, and accessories, and the meat was an important source of protein. When European settlers arrived, they also used the conchs for food and sent the shells back across the ocean where they were popular curios. For many years the shells of queen conchs were sought after for this purpose, and a commercial harvest began. The shells were even used as building materials, ship ballast, and in the foundations of roads.

The Florida Keys have a long history of using the shells for communication between ships and as an instrument. The economy in the 1800’s was largely based on salvaging shipwrecks, and the sailors and “wreckers” would signal using the conch horn. There are still annual conch blowing competitions in honor of this history.

In 1965, Florida passed a law that required the meat of the conch to be used in addition to the shell, which led to an increase in its popularity as a food item. This was spurred on by the growth of tourism and increased international demand. Conchs were originally harvested by divers from small boats using glass-bottom buckets to see the sea floor. Once scuba gear came on the scene, it was much easier for the snails to be retrieved, and by 1966 between 200,000 and 250,000 conchs were harvested a year in Key West. This, coupled with habitat loss, led to a population collapse in the early 1970s that prompted the Florida state government to place a moratorium on queen conch harvests in 1978, and then a total ban on all harvests in 1985. Harvest from federal waters was banned a year later.

The queen conch is still a protected species in Florida and was listed in CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix II in 1992, recognizing it as a species requiring regulated trade and vulnerable to exploitation. Many countries in the Caribbean have implemented policies and quotas to maintain a viable population of queen conch, and research into aquaculture and assisted reproduction is ongoing. The queen conch population in Florida has been making a comeback, but it has been declining in the rest of its range. As of February 14, 2024, the queen conch is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. This may have impacts on the importation of queen conch products, 78% of which go to the United States, and the rules around interacting with the animals in the wild.

How Do You Pronounce “Conch?”

This is a common question in the Keys! The local pronunciation of “conch” is like “konk,” the “ch” has a hard /k/ sound as in “cat” or “character.”

Other “Conchs” in the Touch Tank

Milk Conch

The milk conch, Macrostrombus costatus, is a “true conch” and named for the milky white color of its inner shell. It moves and rights itself using the characteristic stromboid leap. Although they have a similar outward appearance, milk conchs are much smaller than queen conchs. They also have a red and blue ring around their eye that differentiates them from queen conchs.

They are edible, but the effort to harvest the meat and less desirable flavor have made them a second choice to queen conchs. It is becoming more common to see milk conch mixed in with queen conch meat, as the queen conch population has declined.

Florida Fighting Conch

The Florida fighting conch, Strombus alatus, is the smallest conch in the Touch Tank but may be the fiercest. It is named for the aggressive battles between males over breeding. Males fight using their long, trunk-like proboscis, and the winner of the sparring match gets to mate with the female. Fortunately, they are peaceful herbivores the rest of the time.

Horse Conch

The Florida horse conch, Triplofusus giganteus, is the state shell of Florida. These predatory marine snails are the largest gastropods in the Western Hemisphere, able to reach 2 ft in length! They commonly prey upon other snails, including tulip snails, lightning whelks, and queen conchs. Although they are called “conchs,” they are not “true conchs.” They are more closely related to the tulip snails. The shell of the horse conch is a popular curio, and they have been harvested without regulation for many years. It was once thought that these snails had a long life span, 30 or 40 years, but new research has shown that they may live for only 10-15 years. The huge specimens that were Florida icons are now a rare sight, as over-collection and loss of breeding grounds and habitat have led to a decline in the population.